Above: an example of DALL·E-2-generation provided by Bakz-T.

AI alchemy: DALL·E 2 & the future of generated art

Nearly sixty years ago, the science fiction writer Harry Harrison wrote a grim short story about an illustrator who gets replaced by The Mark IX Robot Comic Artist, a machine that can generate full-color narrative artwork on demand. After a bit of programming and a “pneumatic groan,” the enormous contraption spit out a flawless illustration in the style of Milton Caniff, the creator of the “Terry and the Pirates” comic strip. “He could not even pretend to himself anymore that he was needed, or even useful. The machine was better,” wrote Harrison as the obsolete human stands transfixed by this robot-generated cover art for a “Battle Aces” comic book.

I discovered that short story in a long out-of-print paperback collection, a few days before contacting an artist and YouTube creator named Bakz T. Future. He’s one of the lucky creatives granted early access to DALL·E 2, a recently unveiled artificial intelligence system that can perform all the functions of the Mark IX Robot Comic Artist — on a laptop. While we spoke, Future logged into his account and accessed a neural network capable of executing tasks across the very different disciplines of text and image. Future typed “Illustration of fighting Aces airplanes comic book cover in the style of Milton Caniff” into DALL·E 2’s command bar. In less than a minute, DALL·E 2 had generated a series of bold comic book covers with period-appropriate fonts, complete with the blur of motion and explosions in the sky. The AI system hasn’t quite mastered comic book title coherence and overall airplane design, so the final results won’t drive any artists to existential despair. Yet.

“Creativity is about taking something in your head and making it real,” Future told me. “Up until this point, tools like 3DS Max and Photoshop have been the means of getting something from your head to reality. DALL·E 2 is more pure. I don’t need to spend three hours in some program or spend years learning that program. With DALL-E-2, I can face the consequences of my idea. I’m forced to look at it and assess it based on its merit.” Someday soon, these text-to-image AI systems will impact every corner of our creative lives, so I spoke with a few artists who can give us a glimpse of this rapidly approaching future.

“It’s much more expansive than just creating a cool image,” said Danielle Baskin, a San Francisco-based artist who also got exclusive access to this new tool. She compared DALL·E 2 to “spell-casting,” using the AI system to conjure worlds where obsolete copy machines frolic in Xerox Park, doctors take ultrasounds of baby dragons, or commuters ride a train across the Golden Gate Bridge, “The results often elicit a very strong feeling or a jolt of energy that makes my mind shift somewhere else. That is very magical,” she told me, predicting that text-to-image tools like DALL·E 2 will have massive potential for everything from architecture to set design to culinary arts to city planning.

“Xerox Park” used with permission from Danielle Baskin

The research company OpenAI introduced the original DALL·E in 2021, but it quickly refined the model as early users experimented with the tool. DALL·E 2 arrived in the spring of 2022, a series of AI systems working in concert. One is OpenAI’s CLIP (Contrastive Language-Image Pre-Training) model, an AI trained to identify hundreds of millions of images and translate them into text descriptions. When a human prompts DALL·E 2 with an image request, CLIP works as a “text encoder,” helping the AI system understand and synthesize elements of the human prompt.

Next, the AI system combs through hundreds of millions of images classified and compressed in “latent space,” a hidden realm where AI groups millions of images according to their similarities. Latent space is a bit like Hanger 51 at the end of “Raiders of the Lost Ark,” a seemingly endless warehouse with artifacts sorted into crates according to some arcane method that’s too complex to fathom. Finally, the AI system applies an “image decoder” to translate its discoveries into a set of 10 different images corresponding to the original human prompt. Users can even modify these AI-generated images with simple text commands through inpainting and editing functions.

DALL·E 2 is only in preview mode right now, open to a small number of “trusted users” who have already created more than three million images. The company employs text filters and automated analysis to flag images that break the company’s strict content policy that only allows “G-rated imagery.” Users can lose access if they create or distribute images that reflect hate, harassment, violence, adult content, illegal activity, deception, or spam.

Beyond the content limitations, OpenAI has an even stricter policy about artists profiting on images they create, forbidding the use of DALL·E 2 to create NFTs or other commercial ways to “license, sell, trade, or otherwise transact” the generated images. “I’m personally very excited about NFTs,” said Future when asked about possible scenarios for the future of AI-generated art. “The closer the relationship we can get between creator and audience, the better. I want my subscribers to be economically incentivized and rewarded for just being a supporter. They can be along with my journey.”

For creators looking for more freedom, a community of artists and coders have been working to offer open-source tools for creators to use without such strict usage rules. This community has developed AI tools like CLIP Guided Diffusion, Disco Diffusion, and Centipede Diffusion to utilize and reproduce the functionality of DALL·E 2. This community has pioneered the art of “prompt engineering,” designing optimal text descriptions to make AI create better art.

Chris Allen is a digital artist and musician obsessed with this new field. He has spent months working with Disco Diffusion, an open-source tool that accepts text prompts and uses OpenAI’s CLIP-Guided Diffusion neural network to produce custom artwork. While the results can’t quite match DALL·E 2’s performance, thousands of artists have joined the Disco Diffusion community, making digital images, video art, and NFTs.

“Eventually, there’ll be a continuum,” Allen told me, looking ahead to a future when DALL·E 2 is available for all artists to use. “There will be corporate-sponsored access with gated communities. For OpenAI and other companies, that will be their business: inventing cool machine learning things and making them available on a subscription or contract basis. Then there will be this long smear of crazy experimental stuff.”

Allen wrote “Zippy’s Disco Diffusion Cheatsheet,” a constantly evolving handbook that introduces artists to this popular open-source AI system. “I love making the art, and I love sharing what I’ve done,” he said. “I love helping other people. It’s a good feeling to know that I’m helping someone achieve their goals, in the same way that someone helped me.”

Allen has created a series of science fiction-themed digital artworks, NFTs, videos, and films. He showed me “Hybridized Crops,” a work of art created with Disco Diffusion, as well as digital editing and animation tools. He has minted 11 editions of this surreal NFT. In the endlessly looping video, the camera moves like a microscope, zooming deeper to reveal microscopic nanobots inhabiting the veins of a plant, organic and inorganic life co-existing at the atomic level. Allen spent hours generating, refining, and stitching together these images on his home computer, tapping into the mighty processing power of Google’s cloud-based computing services. “Lots of digital is very literal. What you put in is exactly what you get out,” concluded Allen. “With AI, you are just steering the horse and hoping it goes the right way. It’s a very liberating experience.”

“Hybridized Crops” by Chris Allen

Text-to-image AI systems have already been used for film projects and will have a tremendous effect on everything from storyboards to costume design to CGI. In May, Allen won the AiME Award for Best Ai Movie at The Known_Ai Film Festival, a juried film competition that celebrated this emerging art form. His film “The End of the Day” had a similar aesthetic to “Hybridized Crops,” imagining a dystopic future ruled by a rogue solar power company.

The artist Bakz T. Future did a whole video about the innovative and disruptive possibilities of AI systems called “Silicon Hollywood.” “The benefit of these tools is filmmakers can just create,” he said. “They don’t need a team, they don’t need a big budget, and they don’t need to schmooze know the guy who knows a guy. It’s my personal belief that by the end of the decade if you have a great concept for a movie, you’ll be able to make it by yourself.”

This new creative landscape will inspire a whole new legal genre as artists push the limits of fair use with NFTs and these ever-evolving AI systems. Nike and Hermès International have both sued creators for minting NFTs that play with designs by these iconic brands. A federal judge recently rejected artist Mason Rothschild’s motion to dismiss Hermès International’s lawsuit over the artist’s “MetaBirkins” NFTs, a project that reimagined the fashion brand’s handbags with technicolor faux fur. That decision from U.S. District Judge Jed S. Rakoff allowed the historic lawsuit to continue, as the fashion brand tests copyright protections in this new frontier. While OpenAI forbids artists from using DALL·E 2 to create NFTs, I quickly used an open-source AI system to generate my own furry rainbow handbag. Pandora’s Bot has been activated, and legal challenges will multiply as creators use these AI systems to play with iconic designs and other beloved intellectual property.

“Rainbow Handbag” generated by Jason Boog

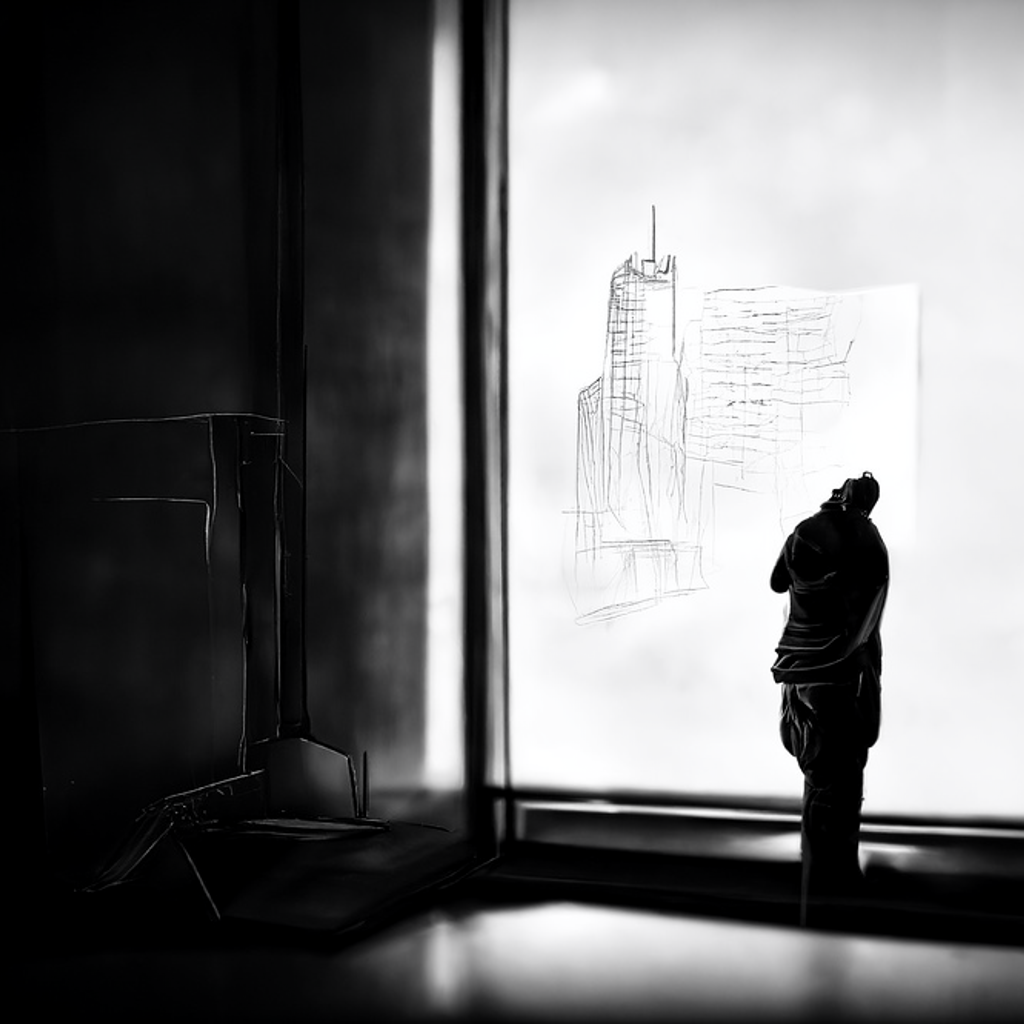

When the Mark IX Robot Comic Artist replaces our hero in Harry Harrison’s short story, the doomed creative inks a self-portrait before leaping to his death. “The artist stood before the window, nicely rendered in chiaroscuro with backlighting,” wrote the science fiction author in 1964, describing this final sketch.

Using the open-source Disco Diffusion on my laptop, I created a whole series of AI-generated interpretations of that illustrated suicide note: the artist dwarfed by the crosshatched city skyline, minimized as a sad shadow, or reflected as a disheveled and skinny figure. These sketches showed me how these unfathomable AI systems classify both human sadness and human creativity, sorting bits and pieces of our reality in the inaccessible realm of latent space.

“Human Shadow” generated by Jason Boog

“Creativity is combining all the resources and tools available to you,” Danielle Baskin concluded. “So I don’t think humans lose creativity when given a new creative tool. It just becomes part of their greater toolkit.” Instead of Harrison’s massive printing machines, we have AI assistants that we can access on a laptop. These neural networks won’t turn us into suicidal button-pushers as Harrison feared. We’ll be full collaborators with these spooky and brilliant alien minds.

Art

Curated Conversations: ALIENQUEEN

SuperRare Labs Senior Curator An interviews ALIENQUEEN about psychedelics, death, and her journey in the NFT space.

Tech

Out of the Vault and onto the Chain: the Evolving Nature of Provenance

SuperRare editor Oli Scialdone considers the social experience of provenance and its relationship with community in the Web3 space.

Curators' Choice

Curated Conversations: ALIENQUEEN

SuperRare Labs Senior Curator An interviews ALIENQUEEN about psychedelics, death, and her journey in the NFT space.