Editorial is open for submissions: [email protected]

63 YEARS AGO, A NON-FUNGIBLE-TOKEN WAS AN ART-WORLD SENSATION. 4 YEARS AGO, IT WENT ON-CHAIN.

www.mitchellfchan.com

Twitter/Insta/Clubhouse: @mitchellfchan

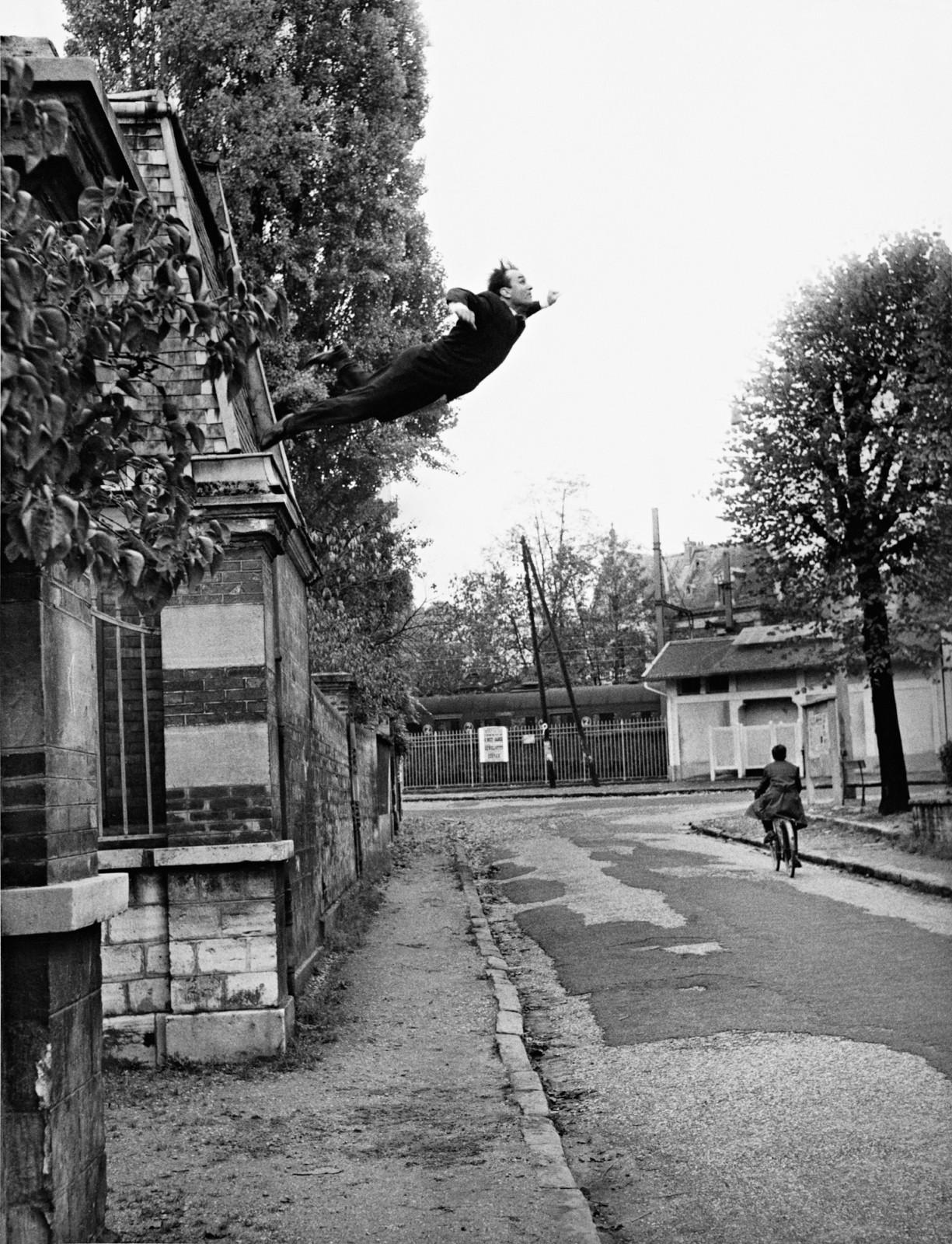

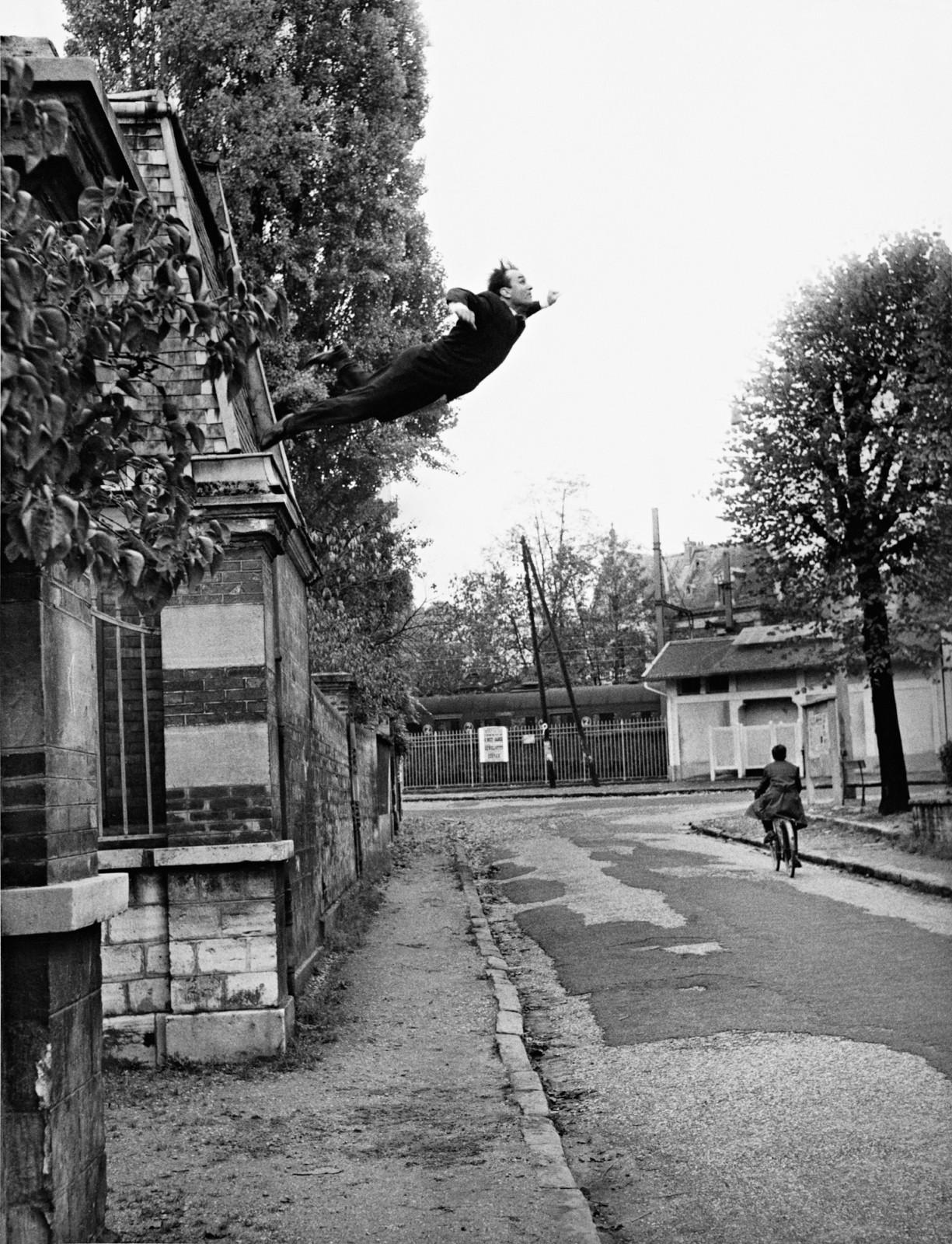

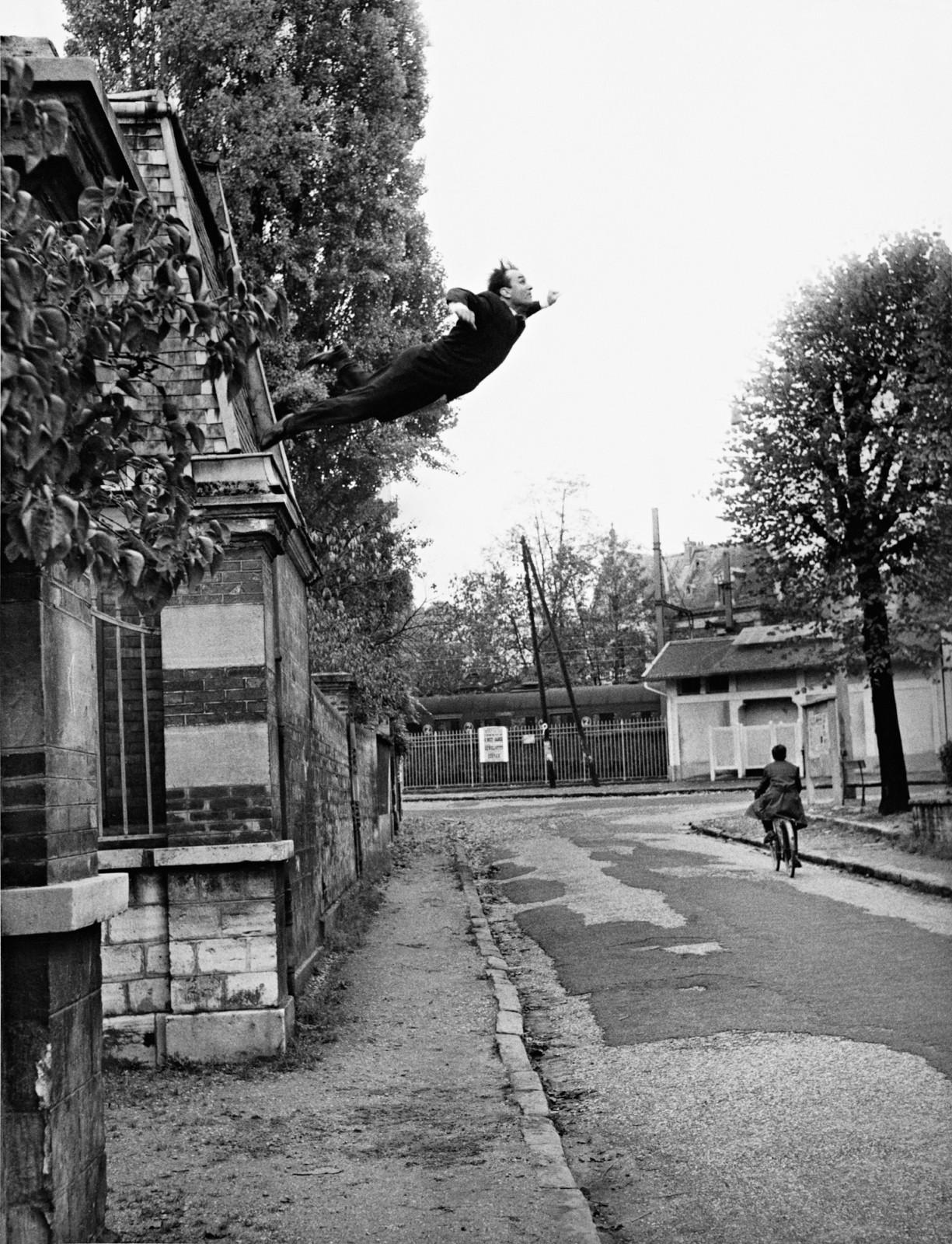

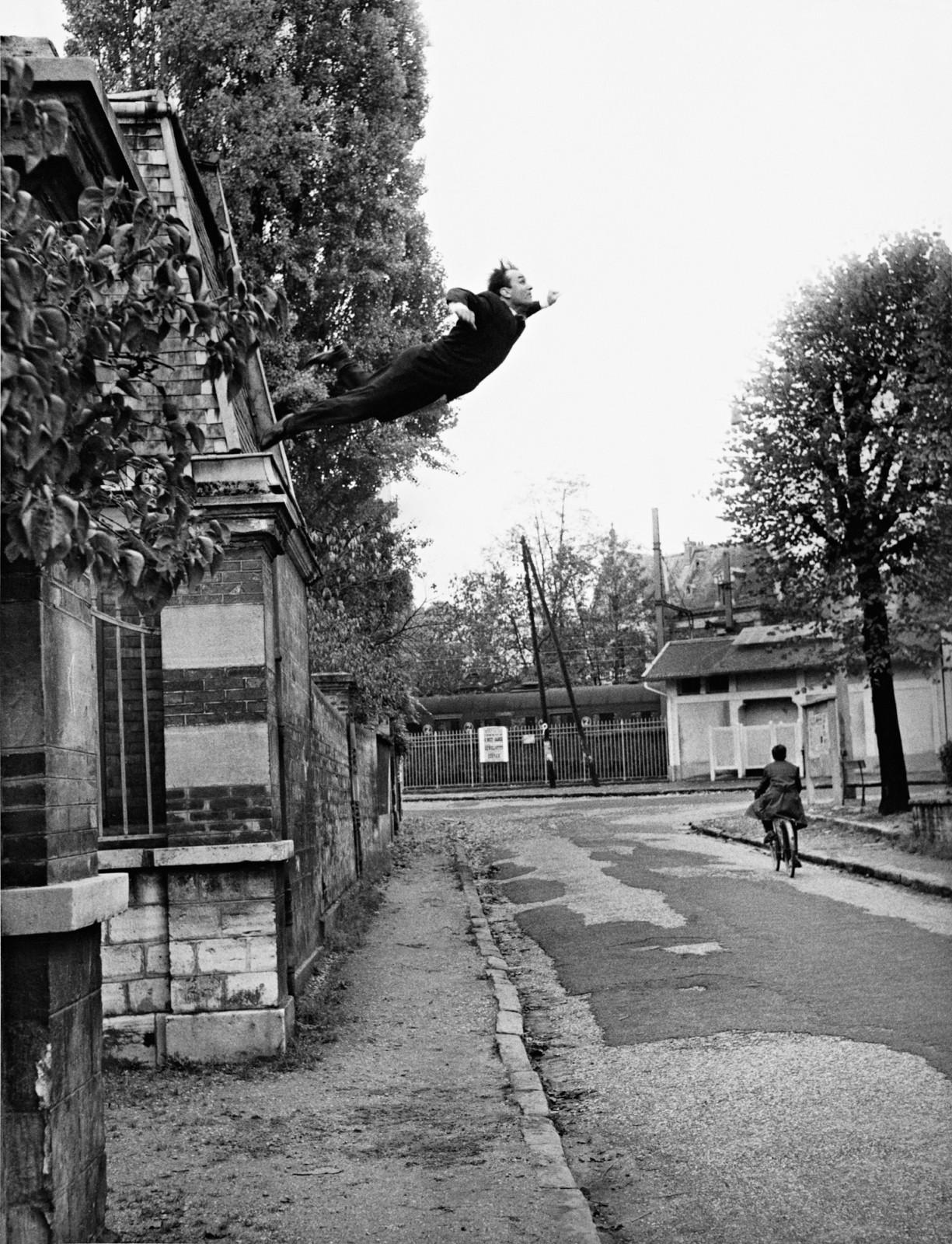

Artistic action by Yves Klein

5, rue Gentil-Bernard, Fontenay-aux-Roses, France

Photography

Photo : © Harry Shunk and Janos Kender J.Paul Getty Trust. The Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles. (2014.R.20)

© The Estate of Yves Klein c/o ADAGP, Paris

Note: the following text is adapted from the video essay embedded above.

Great news: the perfect case study on how-an-NFT-can-be-high-art is here. The embarrassing part? It’s actually been around for over 60 years.

NFTs as super-charged collectibles seems to be a relatively easy concept to grasp. People comprehend the notion of scarcity and the way it drives collectibility. And helpfully, many people can recognize an established practice of physical token collectibles—like cardboard trading cards—moving out of shoeboxes and into digital environments like video games. NFTs, with verifiable scarcity and easy-to-access liquid markets, are easy to understand as a natural evolution of the collectibles.

But the notion that a token can represent a legitimate work of contemporary “high” art is, for some people, difficult to accept. I can sypathize with this, to a degree. To acknowledge NFTs-as-high-art is to accept these two counter-intuitive premises:

- The assertion that the experience of an artwork is not necessarily linked to a material object.

- The assertion that the experience of an artwork is necessarily linked to the concept of ownership.

At first, neither of these statements would seem intuitive for someone who’s invested a significant amount of time wandering through galleries, or who’s paying off art school student loans. However, those with a knowledge of art history ought to recognize that these two arguments were litigated a long time ago. We already settled this, you guys. It was over 60 years ago that one of most celebrated artists of the twentieth century created a shocking—and brilliant—masterpiece that addressed precisely these two points. So let’s revisit it.

I.

YVES KLEIN AND “IMMATERIAL” ART

Let me paint a picture for you. The year is 1958, and you’re in Paris, outside Galerie Iris Clert at 3 Rue des Beaux-Arts. Actually, you’re a ways down the block from there because you are stuck in a long line-up to get in the gallery to see the newest exhibition by art-world sensation Yves Klein.

As you finally reach the gallery, you see that the windows had been blocked out with panels painted an incredible deep shade of blue. This is Klein’s trademark colour. The entrance to the gallery is shrouded with a luxurious curtain of the same hue.

Finally, you’ve made it to the entrance of the gallery. Before you enter, the artist himself hands you a celebratory cocktail—gin, cointreau, and methylene blue—to sip while you enjoy the exhibition.

You enter the gallery, teeming with anticipation, ready to see this newest masterpiece by the art world’s hottest young star, and…

Nothing.

There’s nothing there.

Not even the colour blue.

In fact, prior to the exhibition, Klein meticulously repainted the whole gallery white, just to make sure the space would look as empty as possible.

You stand in the empty space for a while. And a while longer. You leave, making room for the next visitor.

Outside, some people who’ve been through the gallery are confused or even angry. But a lot of them are moved nearly to tears. Albert Camus is here. He’s in awe. He’s written a brief note for Klein:

“With the Void, Full Powers.”

So what’s just happened here? Has Yves Klein just perpetrated the greatest scam in art history? Is this the art world version of The Emperor’s New Clothes?

The answer—and I’m comfortable saying this definitively, because lots of people who have studied art history and who are a lot smarter than me agree—is definitely NO.

These “invisible” artworks, which would come to be known as the zones de sensibilité picturale immatérielle were the apotheosis, the very purest manifestation, of an idea that had been developing in art for decades: the idea that an artwork was an idea or experience that is completely independent of its physical container.

It’s an idea about art that’s worth revisiting in this moment. It’s an idea that might help us to think intelligently and critically about the emerging NFT space. And just maybe, this NFT boom provides a new set of tools and a big group of artists to push this ideaforward.

II.

THE PATH TO IMMATERIALITY

To really understand the meaning of Klein’s Zones (and to really understand the meaning of any artwork, probably) we need to take a deeper look at the history of Klein’s career up to that point, and the history of the art ideas that he was building on.

There are many different intertwining threads of ideas that played out over the first half of the twentieth century. Here’s a three bullet-point history of one of those threads.

- Art used to start with a real thing, and then try to copy it. The more the art resembles the real thing, the better it was!

- Later on, art could start with a real thing, and make it look different! The more ingenious your way of making it look different, the better!

- Finally, art doesn’t have to start with a real thing at all! Art is its own thing! It can be a completely original phenomenon in itself!

Boom. Just wrote your first year modern art history paper for you.

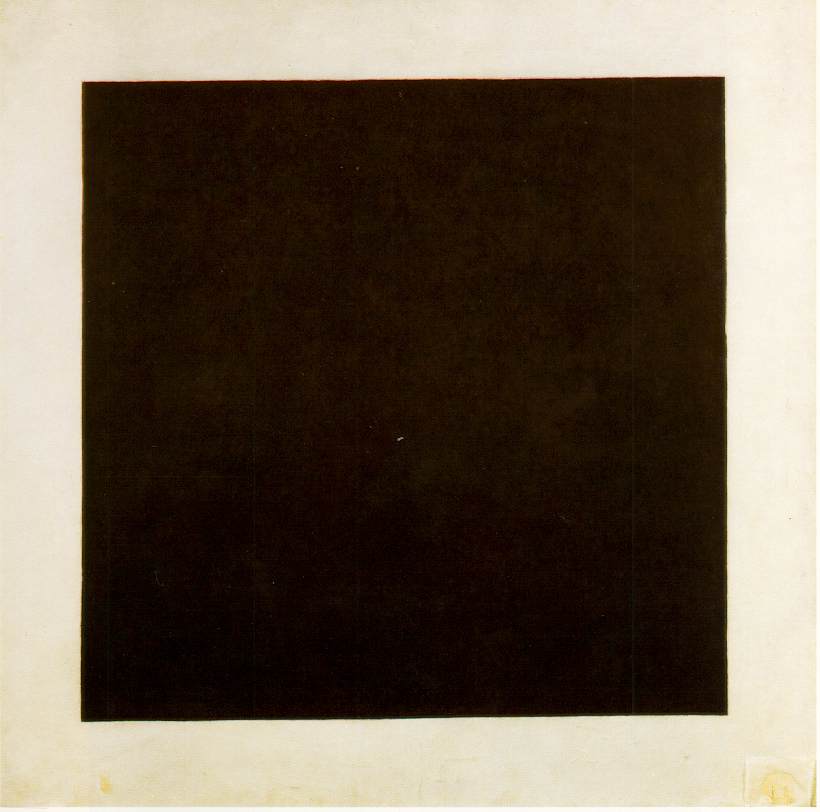

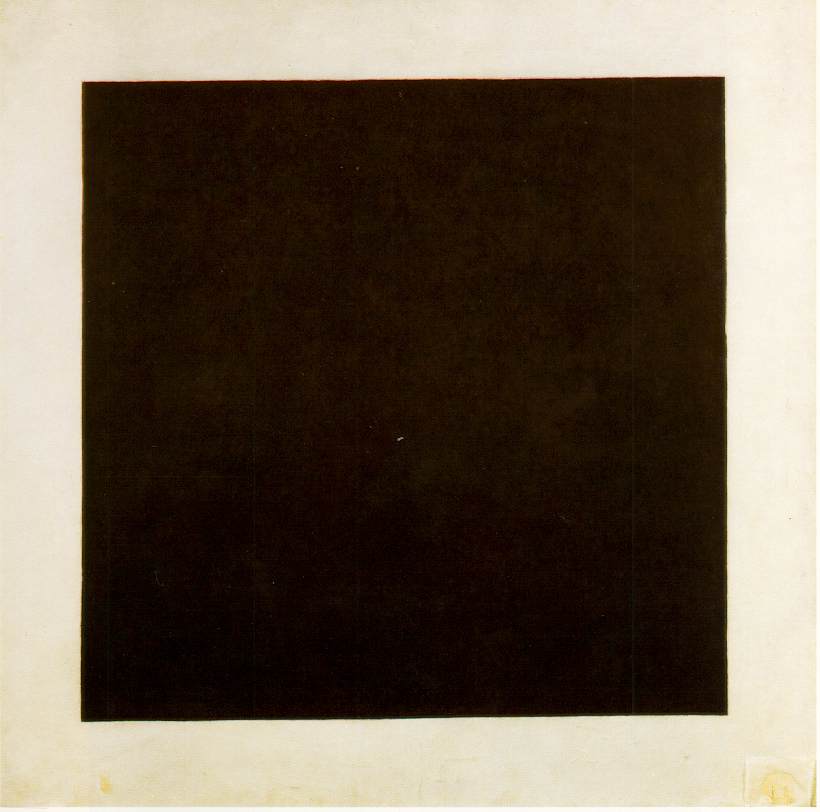

Klein is probably still best known for his blue monochromes. These paintings are about that last bullet point: the idea that art could stop representing things and be its own thing. His monochromes look kind of like some other paintings that were trying to embody the same ideas.

Like this one:

When the Russian Suprematist painter Kazimir Malevich paints this in 1915 he’s trying to really throw down the gauntlet. He’s saying: “No, my painting is not an abstraction of a real thing, it does not represent anything, it is not an imitation of a real-world object. It is simply a black square, to be taken on its own terms. And that’s probably why he titled it simply Black Square and not Black Bear At Midnight.

Klein’s monochromes are definitely inspired by this work, but they push this idea forward a bit, in both their concept and their technical execution. Conceptually, Klein isn’t satisfied with leaving the conversation where Malevich left it, saying this painting is just a painting. He truly believes that his art is a sensation, a feeling. Maybe today we’d call it a state of mindfulness. He doesn’t even want it to be a painting! So he does a couple very smart things with his craft.

First of all, he uses his patented blue (he literally patented this shade of blue). It obliterates the picture plane. It’s so flat, so hypnotic, that if you stare at it, it seems to have infinite depth. You can’t really tell where the canvas is in front of you. Think about it: he’d used a glossy paint, you’d see specular highlights or reflections. You’d always know that there was a surface you were looking at, the glossiness would reveal the picture plane. But with paint this flat, the painting becomes space.

Secondly, he’d mount the monochromes on pegs that pushed it off the wall a few inches, further messing with your ability to perceive it as a flat painting on a wall.

So Klein is desperately trying to get to the point where his art can be just pure sensation. But he has this problem, where no matter what he does, it’s still a more-or-less rectangular thing on a wall. It’s still an object. For him, the physical aspect is holding him back. So Klein is way ahead of where some people are in the NFT debate. He’s not asking if something without a physical aspect can be art. He’s going further, saying that he needs to separate his art from the physical aspect.

This idea of an artwork that is more pure idea and less physical material is sometimes called “dematerialization,” and it’s absolutely crucial to point out here that Klein was a true believer in this. And none of this works if he doesn’t have a long history of exploring these ideas across multiple artworks and exhibitions that he’d invested his whole career into.

Around the same time as he was preparing for the Zones, he was drawing up plans for buildings that would use only pillars of fire and columns of blown air. It’s crazy stuff, sure, but there’s a tidy story connecting the monochromes to this “architecture of air,” and finally to the Zones.

The Zones were the absolute apotheosis of Klein’s quest to present an artwork that was pure idea. Because according to Klein, these Zones weren’t empty. He claimed that they were IMBUED WITH THE SENSIBILITY OF THE COLOUR BLUE. When he presented the Zones at a later exhibition, he stood and loudly declared:

“FIRST THERE IS NOTHING, THEN THERE IS A DEEP NOTHING, THEN A BLUE DEPTH.”

In Klein’s own words, what he achieved with the Zones was: “the creation of an ambience, of a real pictorial climate, one that is therefore invisible.” He claimed that the sensation of the colour blue was there in the room with you, even if they couldn’t see it. He claimed this exhibition would “literally impregnate” viewers with the colour blue. When the visitors to that exhibition got home, they would find that was true in at least one sense: that cocktail you drank at the entrance to the exhibition? It dyed your piss blue.

And because I know Klein had devoted his life to these ideas of immateriality, I believe him. Klein had created an artwork that could contain the “sensibility,” or produce the sensation, of a visual experience without relying on paint, canvas, or any material at all.

OK, so I ‘What does this mean for NFTs???’ cry the enthusiasts and skeptics alike?

Well, first of all, recognizing half-century-old art ideas like this goes a long way to legitimizing the claim that, NO, an artwork does not need to have a physical aspect. And that’s important. Because the Mark Cuban tweet that we opened with in the first segment speaks really only to the concept of collectibility as being separate from physical artifact. I think that if you’re working in NFT art, and you really want to be an artist, it’s important to think about artistic value as separate from collectibility. And Yves Klein is a really great example of someone who truly believed that an artwork was art was an idea, that an artwork was an experience, but that an artwork was NEVER a physical thing.

OK, so our first point is established: the assertion that the experience of an artwork is not necessarily linked to a material object.

But guys… let’s talk about the elephant in the room here. Let’s talk about the MONEY.

Well, this part of the conversation is where Klein graduates from run-of-the-mill CLEVA ART BOI to absolute genius. If you think these invisible Zones De Sensibilite Picturale Immaterielle are fascinating, WAIT TILL YOU HEAR WHAT THESE THINGS COST.

III.

HALF THE GOLD

Here’s a thesis I keep coming back to again and again:

Artistic value MUST be expressed through a system of capital to be considered legitimate.

I’ll unpack that thesis over the course of a number of lectures, the first of which is embedded above, but for now, let’s just talk about what it means for Yves Klein’s Zones of Immaterial Pictorial Sensibility.

The relationship between art and materiality was just one of the ideas that Klein was exploring. As I said above, it’s an idea that I think he pushed forward incrementally, with some of the techniques he used. But the OTHER thing that he was exploring was this question: what does it mean to own an idea?

The Zones of Immaterial Pictorial Sensibility were for sale. And that meant that you could own… that feeling of the colour blue? But if you wanted to own this most immaterial of artworks, you had to pay in the MOST material of currencies. PURE GOLD. That’s right, you could only buy these invisible artworks for pure gold. And PEOPLE DID.

When you handed over your gold for this Zone, you did get something physical in return. You got this:

A receipt. A TOKEN. That acknowledges your legal ownership of the Zone. That’s it.

But wait, it gets crazier. Because Klein recognizes that while materiality is not strongly linked to a sense of connection with a thing, ownership IS really strongly linked to a sense of connection with a thing. And that’s true whether the thing in question is a rookie card or an esoteric art idea.

Once again, a question that’s common amongst NFT skeptics—how can someone feel satisfaction about owning an immaterial thing?—is a question that Klein had moved way past more than 60 years ago. He takes it as a given, and so he actually goes a step further and starts messing with that idea. He understands that ownership fundamentally changes the experience of an artwork, and so now he starts to experiment with different types of ownership.

KIein sets out some complicated rules about ownership of the work. If you want a receipt to say that you now “own” this idea, you have to pay for it in gold. BUT… he says you won’t really own what he calls the “true immaterial value” of the work. It won’t become a part of you. To have that, you have to participate in this ritual.

He says: meet me at the river Seine. Bring the little paper token that you just paid for with 20 grams of pure gold. And burn that token. Then, I’ll throw HALF the gold in the river. And now, and only now, do you TRULY own the artwork.

There are three documented instances of collectors performing this ritual with Klein.

One collector who actually did this described his experience, writing that he had “no other experience in art equal to the depth of feeling of [the sale ceremony]. It evoked in me a shock of self-recognition and an explosion of awareness of time and space.”

It’s interesting to me that “burning” is one of the functions that is, by default, included in NFT token contracts. I know that there are some prominent NFT collectors who have made big money purchases, and then publicly burned the token. I recognize that doing this is typically considered a “flex,” but I’m really curious to hear from these collectors about this experience. I need to know — how did it make you feel? Do you feel like you, too, now own the artwork absolutely and intrinsically?

OK, so that’s a lot about Yves Klein and the Zones. And hopefully, you’ve seen how some of these esoteric conversations that were happening in art around 1960 are really relevant right now. And we’ve seen how Klein’s Zones were, sort of, the original tokenized artwork.

But just as Klein would use his new tools to improve on Malevich’s ideas of abstraction, so were there artists who would use their own new tools to improve on Klein’s ideas of immateriality. And even as blockchain and smart contracts were in their infancy, some artists were already thinking about applying these technologies to conceptual art. I was one of them.

IV.

PUTTING IT ON-CHAIN

If you’ve read this far, it’s probably time I told you a bit about myself.

Over the 15 years that I’ve been an artist, I’ve done two things:

Like Yves Klein, I’ve also been interested in making art out of extremely minimal physical substance. Unlike Yves Klein, I haven’t done it to make an art that’s disconnected from our temporal world, I’ve done it because I’m trying to represent a world which feels increasingly insubstantial.

Like this sculpture depicting a conversation. It’s made out of water vapour because it had stopped feeling like conversations were made of anything substantial.

Or this sculpture: a series of volumetric shape, that seem like you should be able to touch, but they’re really just a two-dimensional string spinning around very quickly. Because my dad had died, but it felt like he was still there somehow.

The other thing I do is I take old art ideas, and I remake them with new technology, because I think it helps me understand both the art ideas and the technology better.

Like this sculpture from 2014, which takes an artwork by Sol LeWitt and turns it into computer code, because I was interested to know if you could still sell an idea at a time when ideas apparently wanted to be free.

And this sculpture, which takes Turner’s Slave Ship and turns it into a little robotic puddle of velvet ropes, because I think an art gallery is a silly place to have a conversation if you’re trying to change the whole world.

But in 2017, both of these things I do came together in a single piece: the Digital Zones of Immaterial Pictorial Sensibility.

In Bitcoin, I saw the ideas of Yves Klein writ large. A bitcoin is a sensibility, a feeling, an idea of financial value that has no reference to the material world. And enough people believe that the idea of Bitcoin’s value becomes fact. Klein would have loved it. Like in Klein’s works, Bitcoin sees the physical as an impediment to true value: paper money can be counterfeited, reprinted, quantitatively eased. An idea has none of those problems.

So it occurred to me that just like Klein was able to advance Malevich’s ideas about abstraction through technical innovation (namely a new type of paint and some unique hanging mechanisms,) I could push Klein’s ideas about immateriality further through the technical innovation of blockchain technology.

A version of the Zones on blockchain, I thought, would be the completion of art history’s push towards immaterialization. Now, not only would the idea be immaterialized, but the very token that denotes it would be too. The ritual which confers ownership would be dematerialized. No meeting at the River Seine for us! The different ideas of ownership—legal ownership and intrinsic ownership—would all be conferred through immaterial blockchain transactions.

More than that, a Zones executed on blockchain would be a sort of manifesto on how blockchain could perfectly distill a certain type of conceptual art.

There were a couple things that I had to do to create the artwork.

First of all, the artwork, or the idea of the artwork, had to actually BE something. Klein’s Zones were, according to him, imbued with the deep blue that he was famous for. But I wanted my artworks to contain a different blue, mostly because Klein literally patented his shade of blue! And so, wanting to be extra careful not to infinge on the patent of Mr. Klein, I went out seeking my own shade of blue to place in my Digtal Zones.

So I travelled to the north coast of Prince Edward Island to create colour studies. After spending a considerable amount of time sketching and deliberating, I settled upon a shade of blue found the exact horizon of between the sky and the Gulf of St Lawrence, three hours before civil twilight. There’s a bit of periwinkle to it. But it’s a distinctly terrestrial blue, almost dusty; not alien and mysterious like Klein’s. It’s a blue that I think people have experienced, and can imagine. I took a photo at the time, but I quickly deleted it. The token was never meant to represent the image. The token was meant to represent the idea.

After the idea, and the content, the rest was easy.

I wrote a white paper, which I called the Blue Paper, naturally. It’s on Github, and I still think that, besides establishing a fundamental belief in the project, and hopefully establishing to the audience a sense of trust in my sincerity, it’s a pretty good blockchain explainer for the artistically minded. If you’re interested in this stuff, I’d immodestly recommend you read it.

I coded a contract. The contract was a modified ER-20 token, as was the style at the time.

As is now standard in ERC721 tokens, it has a burn function, but in keeping with Klein’s ritual, anyone who burns the token also burns half the ETH I received for it initially.

I listed the token on Etherscan as IKB, an homage to International Klein Blue, the colour that Yves Klein patented.

And finally, on August 30, 2017, the project was unveiled in an art gallery: InterAccess on Ossington Avenue in Toronto. After a 90 minute lecture, the contract went live, the artwork was exhibited, and at 8:38PM the very first IKB token, designated by tokenID 0, was transferred.

Shortly after that, the first IKB token was burned. And to this day, I still have no idea who did it, but I hope and believe that they got that experience that idea of ownership and that connection to the artwork.

Time to wrap this up. In the Blue Paper, I made a few predictions about how I thought blockchain tokenization would affect the art world, and I wanted the IKB be a pure distillation of what blockchain could offer art. At the time, I wasn’t thinking about collectibility, the extremely liquid markets, or the financial opportunities that NFTs would present for artists in the future. I was thinking about blockchain as a medium which, in some ways, perfectly distills a specific way of thinking about art.

Because in a lot of ways, an artwork has never been just about the physical thing. Any artwork is a token, a token that connects you to an idea: an idea about the long-past empire, an idea about the person who created it, a political idea, or an idea about the nature of art itself.

And yes, an artwork is a token that allows someone to own that idea. That sense of ownership does imprint itself on the experience of the idea.

So does all this say about NFT artworks today? I dunno. All this history doesn’t mean that all NFTs are actually brilliant exercises in contemporary art. They’re not. Some can be. And if that’s not the direction that NFT culture chooses to go, that’s fine too. The artists in this space have the right to seek out their own ideas and remake the criteria of what art should be about.

But wherever NFT art goes, I think the story of Klein’s Zones—and hopefully, of the Digital Zones of 2017—offers a window to big, exciting ideas that are ripe to be rediscovered and advanced through blockchain technology. And at the very least, the story provides some validation on the basic premise of NFT artworks.

Mitchell F. Chan is an artist based in Toronto. You can see more of his work at mitchellfchan.com

Art

Curated Conversations: ALIENQUEEN

SuperRare Labs Senior Curator An interviews ALIENQUEEN about psychedelics, death, and her journey in the NFT space.

Tech

Out of the Vault and onto the Chain: the Evolving Nature of Provenance

SuperRare editor Oli Scialdone considers the social experience of provenance and its relationship with community in the Web3 space.

Curators' Choice

Curated Conversations: ALIENQUEEN

SuperRare Labs Senior Curator An interviews ALIENQUEEN about psychedelics, death, and her journey in the NFT space.