Lawrence Horn by Harmon Leon

Lawrence Horn: psychedelic digital origami goes NFT

Photographer Lawrence Horn was born in NYC during the 1940s. He made his mark in the photo world through his psychedelic visuals inspired by the bohemian energy of the East Village, which he moved to in 1967.

Horn, whose background is in academics, first picked up a camera in 1973. The game changer was when he discovered infrared film – the format which he primarily shot on until he packed up his photography gear in 1986. Now, decades later, Horn is launching his first SuperRare NFT drop: The Digital Archive. With some of the Archive already available on OpenSea, the project brings his psychedelic work to the blockchain, bridging analog with digital.

Horn’s NFT drop is due to mere fate; synchronicity if you will – the planets in alignment.

His work was hidden in a storage locker, under lock and key since the mid 80s, and it was only because of a chance encounter that his photography is now being rediscovered after more than 35 years.

But more on that later…

Psychedelic Without Drugs

If you look at Horn’s trippy, color-sprayed photos, it’s hard to believe that the man stopped taking drugs in 1971.

“I had tried psychedelics a few times,” he explains. “I said, ‘I get it. I don’t need being high – it’s counterproductive.’”

Infrared photography became Horn’s drug of choice. The medium allowed him to have psychedelic trips–minus the acid.

“My psychedelic experiences always were focused on nature or outer reality,” Horn says. “I didn’t go inside myself because that was classic archetypal mush. I wanted to find something that I could embody my ideas [with], not just write about them.”

For Horn, infrared is a heightened sensory experience; where energy erupts, and color is intensified and radiates out, capturing the moment a heat wave explodes into light.

Infrared makes part of the invisible spectrum visible.

“It doesn’t make the cosmic world come into focus, but in terms of a retinal experience, it’s a frequency that we can’t see, but we can feel as heat,” he says. “So, we have a synesthetic experience.”

Horn would interplay his process by utilizing crystal filters to double the images – while the atmosphere at sunset would act as a light filter and create auras, depth, and shades of color. “The third eye allowed me to lock down and understand energy and nature at a more sublime or spiritual level,” he says. The end result: “An engraving of a specific type of energy that is solar and becomes visible through the film.”

Into the Storage Locker

Before dropping the mic on the photography world in 1986, Horn’s final project was capturing the East Village art scene.

“I had photographed Warhol. I photographed Basquiat. I photographed Keith Haring,” he says. Additionally, Horn photographed Richard Hambleton, a key street artist of the ‘80s whose eerie shadow-creations was one of Banksy’s main inspirations. (Hambleton also outlived his contemporaries – but never got the eternal fame that the others did.)

For Horn, this seemed like the place to bookend his photography career.

“I was going back to the East Village and doing my thing with the artists.” In 1986, Horn took his entire body of work – roughly 6,000 slides – and put them away in the storage locker, closing the curtain on his photography career.

“I had done it. [I said,] ‘I’ll store it very carefully. And let’s see what happens,’” he expresses. “I was really not interested in galleries,” Horn explains, which makes this Emily Dickinson-esque construction all the more poetic. Rather than change for the art market, he decided to put his work to rest until the art market caught up to him.

Thus, into the storage locker went the photos. And that’s where thousands of Horn’s slides remained for almost four decades.

A Vivian Maier Moment

“My temple is Tompkins Square Park,” says Horn – referring to the inspirational patch of nature in the Lower East Side. Galleries once dotted the park’s circumference, filled with the works of Basquiat and Haring.

Since Horn is now retired, he spends his days enjoying the scene through fresh, but experienced eyes. “I go to the park where I have a combination of nature and culture and birds and kids and memories.” On one such sojourn, in the summer of 2020, Horn encountered a woman sitting on a bench drawing in a notebook.

“I noticed something about her,” he says. “It’s very hard to describe. I tend to see auras. I tend to see vibrations; not colors or anything, just vibes…that’s how I approach my photography. For me, a girl sitting on the bench is part of nature.”

Horn struck up a conversation. The woman turned out to be a roommate of Ryan Hall, the man behind the Bustani Project.

This chance park encounter led the woman to show Horn’s portfolio to Hall. After seeing the photos, Hall realized he had just walked into a Vivian Maier-esque moment. He suggested that they go to the storage locker and look through the archives.

“It was a very cramped space. And all I had was a loupe,” says Horn. “I held up to the light 6,000 slides.”

Horn had never really reviewed his photo slides when he originally shot them. “I flipped out,” says Horn. “I was blown away by the slides, as was Ryan, as most people were, because these were done in the early eighties.”

When Hall looked at Horn’s images, the first thing that caught his attention was the other-worldly colors. And then: “It wasn’t until a few weeks later that I started to focus on the subject matter and ask questions about the imagery,” Hall says. “That’s when I realized this body of work was unlike anything I had ever seen or heard of before – almost every single image was historical, complex, mystical, and radiating crystalized solar vibrations.”

The other discovery Hall made was Lawrence’s living scenario. He shared a cramped apartment with an old friend – where he was sleeping on a wooden platform with an air mattress on top. At night, he had to step over his friend, who slept in the living room, just to get to the bathroom.

“It was extremely difficult to see him in that situation – but he never made a single complaint about it once,” says Hall. “He loved being in the East Village, even if it meant being in that situation.”

Digital Origami

For their first NFT drop back in November, it took Horn and Hall four months to go through the slides. The outcome: “All sixty sold out in three hours when Ethereum was pretty high,” says Horn, who previously never knew what an NFT was. “It was amazing.”

“He’s happy to have upgraded,” says Hall. “I know he’s beyond excited to really settle into a new home. We’re hoping for a big breakthrough soon.”

The upcoming SuperRare drop involves five slides.

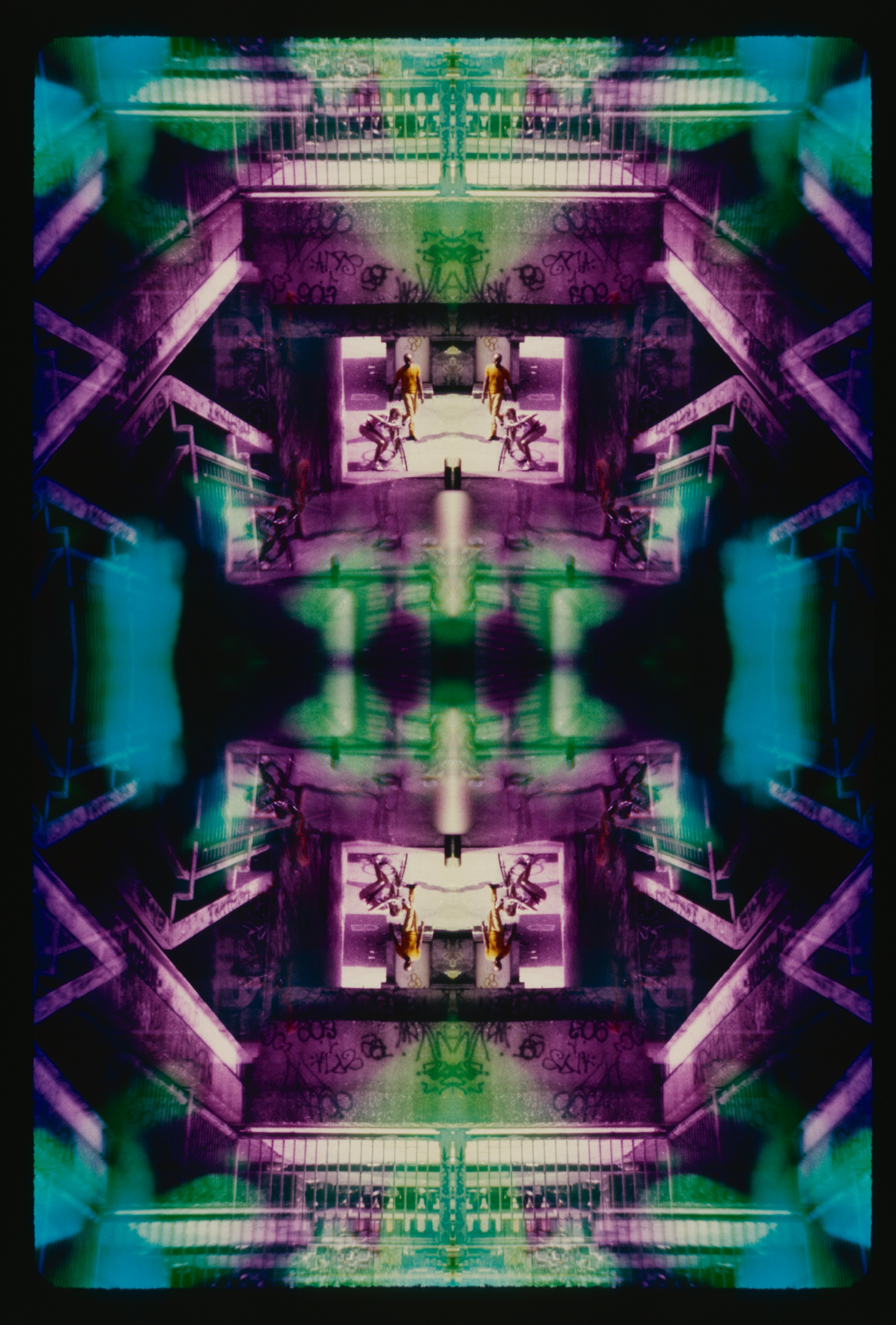

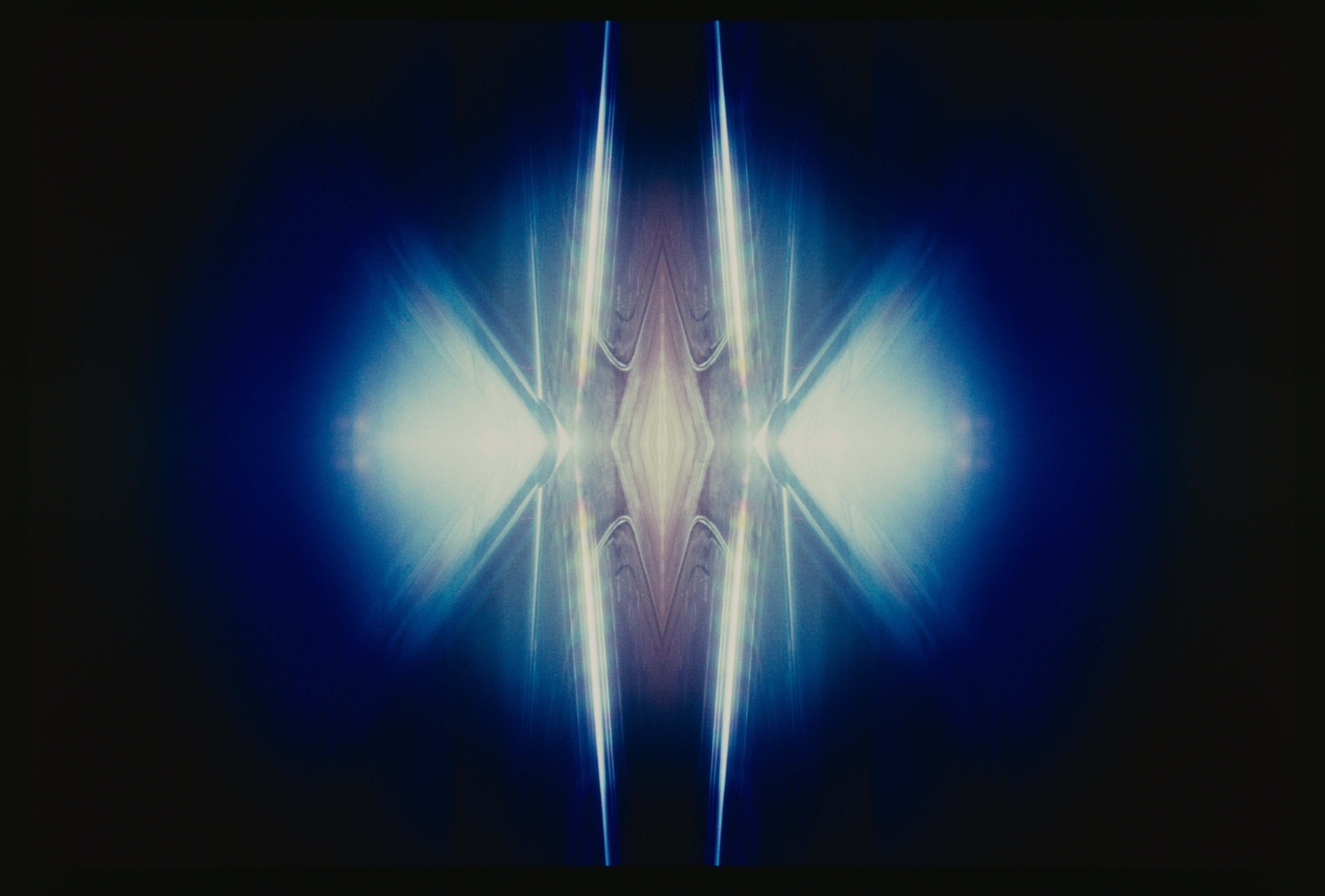

The distinction from the previous drop: Hall had a vision on how the digital could interface with the images. The process involved putting Horn’s images into Photoshop, and then taking either side and copying and pasting it onto the other side; thus, blending analog and digital.

Hall coined the process as ‘digital origami.’

“It’s folded once and then it’s folded again, so that every single side is supported,” says Hall. “It’s literally just making it symmetrical.” The result creates an entirely new psychedelic effect that evolves Horns ‘73-’86 photo work into the NFT world. “What we’re doing is so new that there’s no pre-established horizon,” says Horn, “We’re taking a deep cut into nature, and we are using the fold to liberate that original energy from the eighties.”

The Golden Egg

Horn feels that his photos that were locked away in storage for over 35 years have now aged like a fine wine. “This is more than psychedelic–this is transformative,” he says. A good example of this analog/digital technique is the golden Faberge egg-looking creation. Originally, this was an infrared photo of a clump of trees in Central Park that Horn photographed at sunset.

“I don’t know how, but it became a golden egg surrounded with diamonds,” professes Horn. “By folding the image, it actually released the energy, which was not visible in a single slide. That to me is magic,” Horn says, stating it blew his mind (in a good way) when he first saw the results. “We created the egg from living nature, spontaneously…It’s really far out to think about it.”

And the timing and experience of meeting Hall has opened new potentials for Horn.

“I have 5,000 slides,” concludes the 78-year-old artist. “Each slide can take eight forms. You can imagine the quantity and quality of things that can come from this.”

Harmon Leon is the the author of eight books—the latest is: 'Tribespotting: Undercover (Cult)ure Stories.' Harmon's stories have appeared in VICE, Esquire, The Nation, National Geographic, Salon, Ozy, Huffington Post, NPR’s 'This American Life' and Wired. He's produced video content for Vanity Fair, The Atlantic, Timeline, Out, FX, Daily Mail, Yahoo Sports, National Lampoon and VH1. Harmon has appeared on This American Life, The Howard Stern Show, Last Call With Carson Daly, Penn & Teller’s Bullshit, MSNBC, Spike TV, VH1, FX, as well as the BBC—and he's performed comedy around the world, including the Edinburgh, Melbourne, Dublin, Vancouver and Montreal Comedy Festivals. Follow Harmon on Twitter @harmonleon.

Art

Curated Conversations: ALIENQUEEN

SuperRare Labs Senior Curator An interviews ALIENQUEEN about psychedelics, death, and her journey in the NFT space.

Tech

Out of the Vault and onto the Chain: the Evolving Nature of Provenance

SuperRare editor Oli Scialdone considers the social experience of provenance and its relationship with community in the Web3 space.

Curators' Choice

Curated Conversations: ALIENQUEEN

SuperRare Labs Senior Curator An interviews ALIENQUEEN about psychedelics, death, and her journey in the NFT space.