“Atali’i O Le Crezent” set photos by Belinda Bradley

Making home immortal: dance and longing in Brendan Canty’s “Atali’i O Le Crezent”

“An NFT should be more than a promise to make art.”

Villa Junior Lemanu begins to dance in the beginning of the short film “Atali’i O Le Crezent.” As Irish electronic artist Daithí starts to play, Lemanu’s cheeks puff with air, his spine arches backwards, he bares his teeth as he undulates alone in the living room of his childhood home. In one shot, he winces as his right arm raises up overhead in a gesture that makes it look as though he is ripping his own heart from his chest in excruciatingly slow motion. Although the scene is brief, the camerawork and Lemanu’s facial expressions seize the viewer; it is intimate, it is painful.

It is the union of dance and film, a visual exploration of identity and displacement shot by director Brendan Canty.

A moment from this film has just become available to purchase as an NFT on SuperRare. Proceeds from the sale will fund post-production so that Canty can polish the project and present it to the world. Whoever buys the NFT will own more than just the digitized climax of the short film: They will also be listed as an executive producer in its credits and on IMDb.

“Atali’i O Le Crezent – Short Film” by Brendan Canty on SuperRare

Canty’s eagerness to share credit for his short film makes sense given how highly he values his projects. “You’re asking someone to buy your piece of art,” Canty explained to me over a video call. “I think an NFT should be more than a promise to make art. We’re trying something new here, and that experiment is a part of the process.”

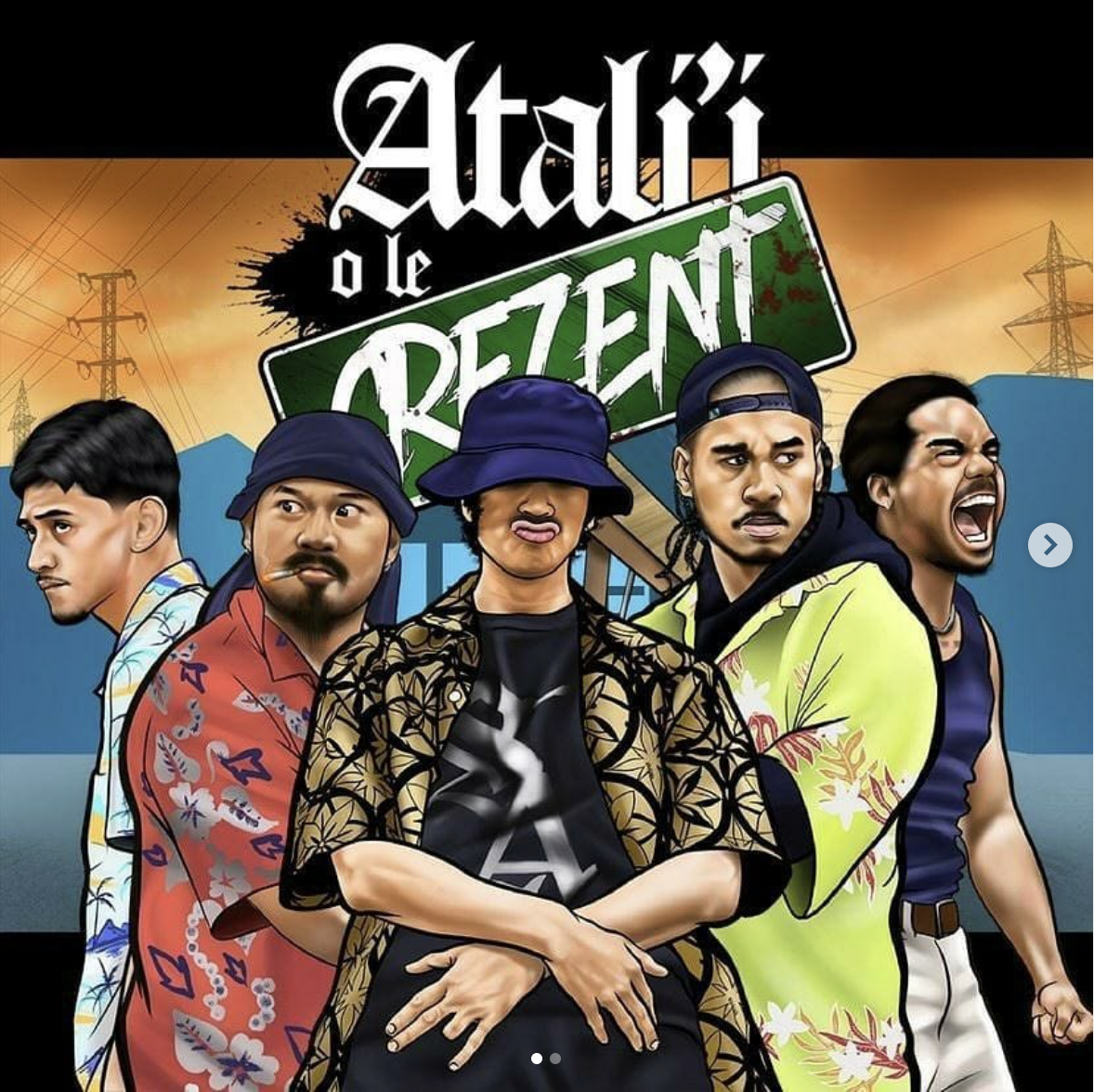

“Experiment” is a word that Canty used frequently when describing his latest short film. He acknowledges readily that most people still imagine cartoon pictures of apes when they think of NFTs, and that the online art scene is often rife with cheeky references to memes. Film is a fairly new medium to join Web3, and Canty knows that he’s wading into uncharted territory. However, he feels certain that he has a crowd-pleaser here, sure to intrigue avid NFT collectors and cinephiles alike. Another bonus? “Atali’i O Le Crezent” (or “sons of the crescent” in English) has already been shot, and its blend of dance, camerawork, and storytelling pack a wide berth of ideas into one small package.

In fact, referring to the work as merely a film feels crass.

“I just didn’t know what to do. It was really heartbreaking.”

Originally conceived as a play, “Atali’i O Le Crezent” is steeped in the cultural tradition of dance, something that its creator and actor, Lemanu, says was second nature to him growing up in South Auckland. The crescent-shaped region’s demography is primarily Polynesian and Maori, and incomes are generally lower than other parts of Auckland.

Throughout the opening montage, Lemanu’s hand gestures at times reflect movements akin to some of the traditional Samoan dances that he grew up with. Other times, his dancing is more abstract; pure improvisational movement meant to convey an intense rush of emotions: grief, joy, loneliness. “With me, I grew up doing Samoan dancing, it’s just part of the culture,” he explained to me. “As I was going through high school, I got more into street dance because that’s what was popular, it’s what my friends were doing.” Both styles are blended in the interpretive dancing we see in the film, a calling card for the memories he made from boyhood among cracked sidewalks and plastic swing sets.

While interpretive dance might not be something the casual NFT collector is familiar with, Canty is mindful to propel the story with visual cues. Wide shots of power lines, empty streets with chain link fences, and open skylines above crowded freeways tell the story of lower income suburbia, and signal a disconnect. Though the play was an ensemble piece featuring Lemanu and four other young men, he performs a one-man show in the short film, reminiscing about his childhood friends in their absence, inhabiting a world that feels at once familiar and otherworldly, even apocalyptic.

The tone of the film is owed partly to the panic from which it was originally conceived. Early in the pandemic, Lemanu took a call from his sister: Their parents and the rest of the homeowners in their neighborhood had received letters from the local housing department warning that the neighborhood would be cleared sometime in the future in order to expand a nearby freeway into the more affluent central Auckland.

Lemanu felt helpless as his parents and neighbors were forced to consider moving. “I just didn’t know what to do,” he said. “It was really heartbreaking. It’s always the same sort of communities that have to be forced out of towns through gentrification.”

“Atali’i O Le Crezent” set photos by Belinda Bradley

Struck by the prospect of losing the place where he was raised, Lemanu scrambled for ideas to immortalize it through art. Initially, he admits that his plans were more elegiac, like interviewing locals and asking for their reactions to the pamphlets that had been mailed to them. Collaborating with four other creatives from the area, he developed his ideas into a play suffused with humorous dialogue and carefully-choreographed dance. Gradually, the project’s tone shifted from somber to celebratory, focusing on the positive energy and camaraderie of his town. Lemanu wanted his play to feel authentic, and he knew that the humor and dialogue filled with inside jokes and references to local celebrities would resonate with viewers.

“He wanted the audience to fear for us from the start, then he wanted the audience to fall in love with us.”

What he wasn’t expecting was for Brendan Canty to take interest in his performance at the Pacific Dance Festival. He had been spending time in New Zealand visiting family (Canty is from Ireland, but his wife is a “kiwi,” or New Zealander), and he ended up staying there for a year as the Covid-19 pandemic shook the globe.

Canty happened upon Lemanu’s play at a time when he had felt his confidence flagging. The acclaimed director is known for short films such as “Christy,” as well as music videos, like Hozier’s “Take me to Church.” However, he admits that as the trip to New Zealand wore on longer than anticipated, he felt isolated. Most of his works have been shot in Ireland, and he was begrudgingly coming to accept that he might leave New Zealand without having started any new projects.

“I didn’t know what I was getting into,” he reflected on his visit to the Pacific Dance Festival and his response to Lemanu’s play. “It was like looking at a culture that on the surface looks so far removed from where I grew up in the suburbs in Ireland. But it really connected with me and I think I had been searching for a bit of a connection in New Zealand. I was smiling ear-to-ear.” He knew right away that the inspiration he had been seeking was there:

“When I saw it, I knew ‘I want to adapt this. Is the structure just for a play, or can I make a film like that?’”

“Atali’i O Le Crezent” set photos by Belinda Bradley

Canty approached Lemanu, a stroke of luck as the pandemic forced the play’s tour to a halt. Turning the play into a short film had always been Lemanu’s contingency plan, so he readily agreed to Canty’s proposal to work together, and was impressed by how quickly he was able to write up the screenplay to direct the project.

“I’ve never approached a film like that; virtually all of the dialogue in the film is improvised through Villa [Lemanu],” Canty reflected. The new approach allowed them to focus less on narrative and more on emotional connection with the viewer. “In our first meeting, I asked him how he structured it, and he said it was simple: he just wanted the audience to fear for us at the start, then he wanted them to fall in love with us, and once they’d fallen in love with us, he wanted to tell them our message, and then he wanted them to be sad to see us go. And I was like that is such a brilliant, simple structure! Not based on anything but feeling—so cool!”

With filming completed in a span of a few days, the next challenge was obtaining funding to complete post-production and get exposure. Fortunately, Canty has already had some success selling NFTs on SupeRare, and realized they could take the product they already had and use it to keep momentum going. Lemanu was new to the NFT space, but readily agreed to minting an NFT with their footage. NFTs that aim to raise money to produce a film have previously been sold on SuperRare. The Minted Series has been raising funds from recent sales to create a documentary about NFTs, riding the wave of popularity that they have enjoyed in the past few years.

“Atali’i O Le Crezent” set photos by Belinda Bradley

In fact, NFTs are becoming an increasingly popular means of raising money to fund causes from wartime relief in Ukraine to funding the creation of a meta-world by FEWOCiOUS, a pioneer of the NFT space. Part of what has made NFTs so popular is the celebrity support and large quantities of revenue that gets poured into them. Canty is confident that his film can join the ranks of projects made possible by fan engagement, especially since he already has all the material he needs and can sell a “sneak peak” of the project.

“Our people don’t need saving. They’ll be okay.”

“Atali’i O Le Crezent” is ambitious outside of its funding goals. Sharing the story with as big an audience as possible remains vital to Canty and Lemanu, and the ability to amplify the struggles of a small community in an isolated island nation through digital space may introduce something fresh yet familiar to viewers across the globe. By the end of our interview, Lemanu was more reflective about the scope of his piece.

“At first, I had this idea about how to stop gentrification,” he said of the process of talking to other theatrical performers and Auklanders about the experience. “But I think the more I discussed where the script could go, I realized that it’s all inevitable and it’s bound to happen. At the same time, our people don’t need saving. They’ll be okay, and I think that was a good reminder for me going into this work.”

The final scene of the film, which is also the NFT that Canty will be selling, takes place in what Canty refers to as “the wasteland,” a weed-strewn field adjacent to an electrical substation only a few minutes’ drive from Lemanu’s parent’s home. Like Lemanu’s neighborhood, the substation was once a series of homes that were ripped down to meet the city’s growing energy needs.

The humor and cheekiness from earlier in the film fade with the light of day, leaving only movement and skyline as Lemanu lists the things he loves about his neighborhood, from “shoes on power lines” to “the kitchen where Mom used to make something sweet.”

The two versions of the story, play and short film, feel to Lemanu like a step through time. “The play is almost like the moment before the film; all the boys are still there, and we’re all celebrating it together. And in the film, everyone’s already left.”

Lemanu stops dancing as he completes his monologue. With a backpack slung over one shoulder and his eyes fixed somewhere beyond the camera, he falls silent and walks away.

“The end is a bookend to the opening,” Canty explained, “At first it’s him in his living room worried about all this. In the end, it’s gone now, but there’s acceptance. And a longing.”

Art

Curated Conversations: ALIENQUEEN

SuperRare Labs Senior Curator An interviews ALIENQUEEN about psychedelics, death, and her journey in the NFT space.

Tech

Out of the Vault and onto the Chain: the Evolving Nature of Provenance

SuperRare editor Oli Scialdone considers the social experience of provenance and its relationship with community in the Web3 space.

Curators' Choice

Curated Conversations: ALIENQUEEN

SuperRare Labs Senior Curator An interviews ALIENQUEEN about psychedelics, death, and her journey in the NFT space.