SuperRare Labs Digital Editor Shutong Liu, alongside collectors Broke0x and EternalPepe, ask socmplxd about his practice, inspirations, and his plans for the future.

TIME EVOLUTION COLLECTION: Beeple and TIME magazine collaborate for two live auctions on SuperRare

TIME EVOLUTION COLLECTION: Beeple and TIME magazine collaborate for two live auctions on SuperRare

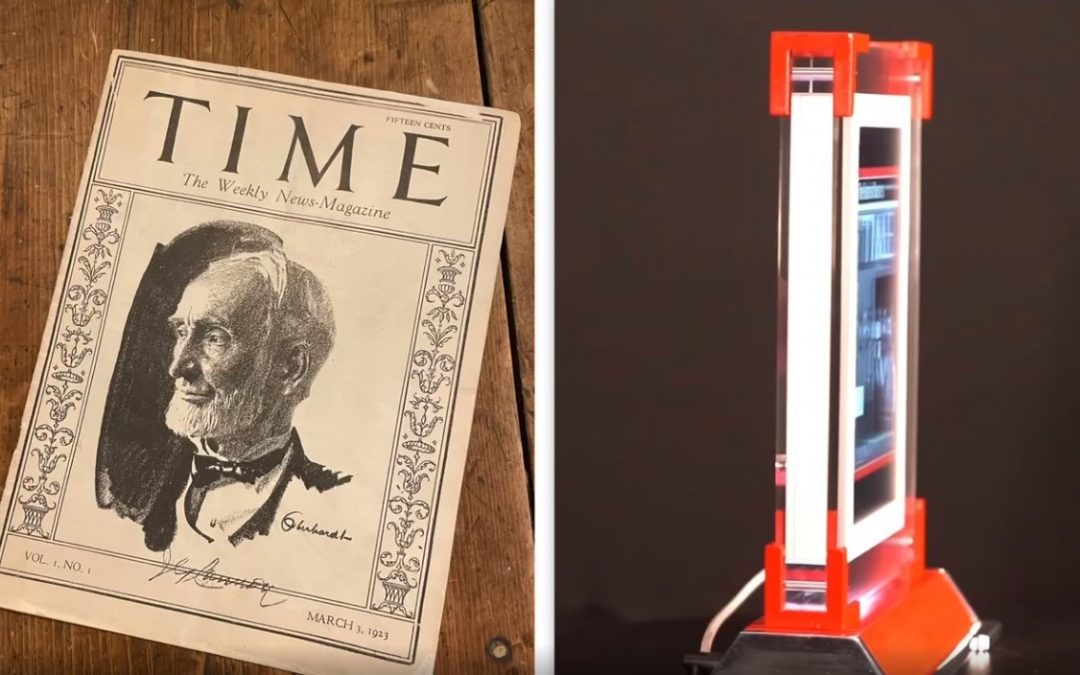

TIME Magazine has announced an exciting auction on SuperRare highlighting two important pieces from their archives: TIME’s first issue from 1923 and a more recent cover by an individual who’s been at the forefront of the digital art movement for more than a decade, artist Mike Winklemann (aka Beeple).

The highest bidder for the first issue of NFT, which can be found here, will also receive a physical copy of the issue, which does not exist outside of museums, libraries and a few private collections.

The winner of the Beeple Cover NFT, which can be found here, will also get the physical piece seen in the NFT as part of the purchase too. The red is in homage to TIME’s “Red Border.”

With nearly 100 years between the covers, these auctions are running simultaneously now and will continue through this Friday, May 21st, with the first issue auction ending at 9PM EST on Thursday and the Beeple piece auction ending at 9AM EST on Friday.

On the TIME first issue

The auction of TIME’s first issue, originally printed in 1923 and sold for 15 cents, comes with a copy of the actual near century old issue.

“In 1923, two young entrepreneurs launched a publication that would disrupt their industry and come to define and in many ways help shape the century to come,” said Edward Felsenthal, Editor-in-Chief & CEO of TIME.

“What I love about TIME’s first cover is the craftsmanship used to create it – a lithographic crayon portrait and hand-drawn line work,” said D.W. Pine, Creative Director of TIME. “As TIME has shown for nearly half a century, history can be made within its iconic border whether the cover subject is rendered in oil or acrylic, photograph or line drawing, 3D render or cut paper or sculpture. The variety of presentation matches the variety of subjects.”

The portrait itself is of then-Speaker of the House Joseph Cannon and was created by artist William Oberhardt two years earlier as a commission for the government. It came to be so widely loved that it was selected to be placed on the top of the 1939 World’s Fair Time Capsule.

“Today, what began as a print magazine mailed to 9,000 subscribers reaches a global audience of more than 100 million across multiple mediums,” Felsenthal said.

On the TIME Beeple issue

“For our May 10th / 17th 2021 issue, artist Mike Winkelmann (aka Beeple) wanted to take our readers inside his “canvas” to depict the stratospheric acceleration of the digitization of our world by creating an image that focused on his artistic process,” Pine said. “The cover image depicts his actual computer interface mid design, complete with a wireframe render of a figure interacting on the left and a more complete version on right.”

The artwork was developed using Cinema 4D and OctaneRender software that is powered by nearly a dozen Nvidia graphics cards.

“People have been creating digital artwork for the last 20 years and it has just as much craft, message, intent, as anything made on a canvas and has just as much ability to affect people emotionally and intellectually,” Beeple said. “It has been exciting through NFTs to see people start to realize the value of this type of work and I think we’re just at the beginning of the next chapter of art history.”

Tech

AI art promises innovation, but does it reflect human bias too?

Can technology exist without the influence of human prejudice?

Curators' Choice

Curated Conversations: Botto collaborates with Ryan Koopmans

Ryan Koopmans and Simon Hudson, BottoDAO’s Operator, speak about how this collaboration came about, how it went, and reflect on its aftermath.