SuperRare Labs Senior Curator An interviews ALIENQUEEN about psychedelics, death, and her journey in the NFT space.

Post-Photography and the Poetics of AI: How Blake Wood’s Uncanny Photographs Capture Intimacy Without a Camera

“Pink I” by Blake Wood, 2022

Post-Photography and the Poetics of AI: How Blake Wood’s Uncanny Photographs Capture Intimacy Without a Camera

Blake Wood, photography by Jesse Jenkins

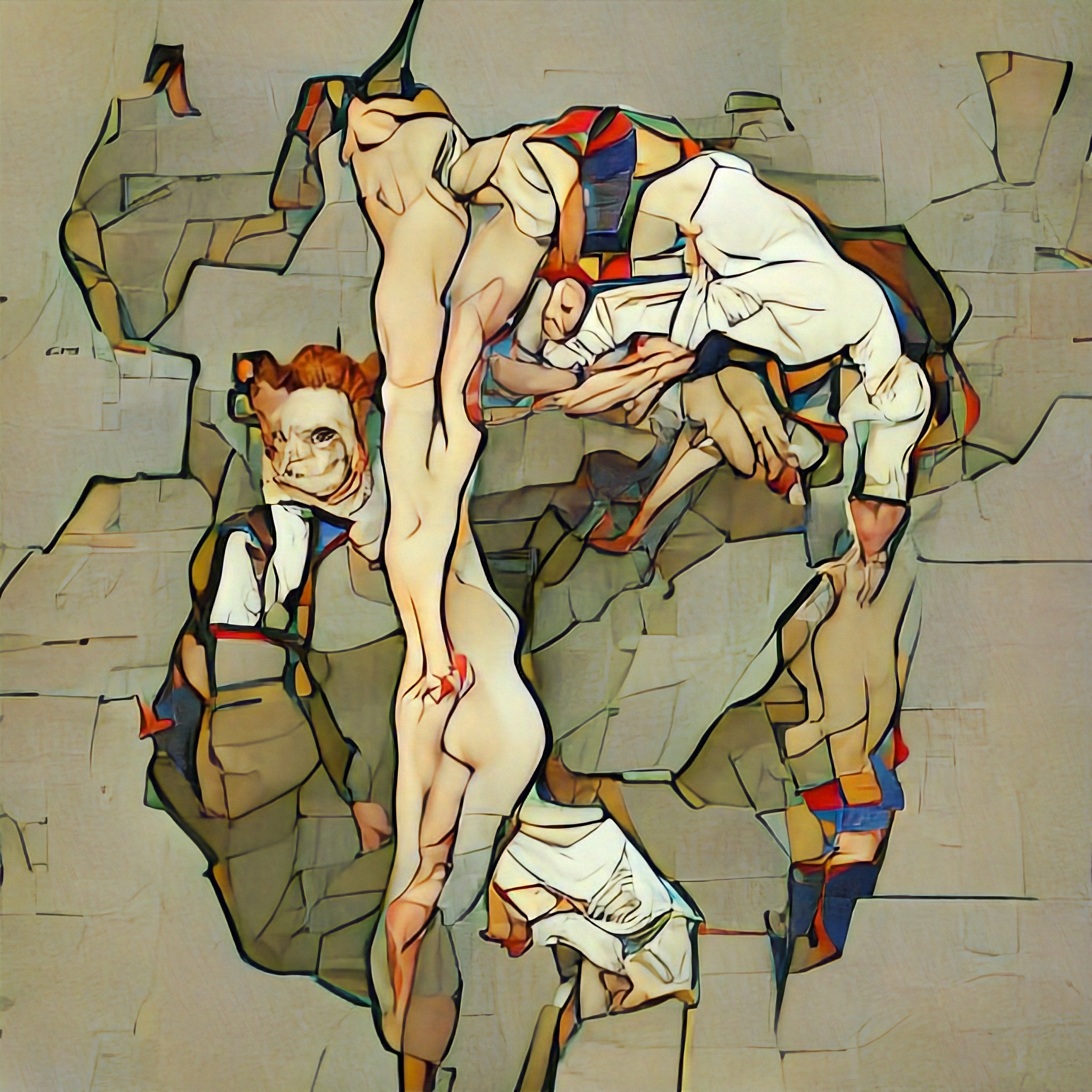

When first encountering Blake Wood’s AI photographs, an untrained eye might register them as film or digital photographs depicting intimate images of queer relationships; whether of friends or lovers, the emotiontal relationship between the artist and subject shines through every frame. But these evocative photographs are created without a camera or a human subject.

An accomplished photographer, Wood uses AI prompting to generate these photographs, His years of experience shooting informs his instruction process down to the lighting and composition. The resulting AI-generated photographs are hyper-realistic and charged with emotion. If previous art movements were concerned with the erasure of the artist’s hand, Wood’s photographs conceal the machine’s touch.

When photography was first introduced into the art world it created waves of antagonism; its ultimate acceptance took time as it propelled new art movements that led to a cultural and intellectual shift in the democratization and perceptions of what art can be. Historically the introduction of new technologies always forces viewers, collectors, and artists out of their comfort zone. Art movements are revolutions of perceptions, and the boundaries of our society can be seen in what we define as art. Exploring the collaboration between humankind and machines, AI artists like Wood are challenging the seemingly innate relationship between art and humanism and our very perception of what is real.

Wood’s work has been featured in international media outlets, including Vogue, The New York Times, The Guardian, i-D, Vice UK, and Dazed.

“Fields II” by Blake Wood, 2022

Mika Bar On Nesher: How would you describe Post-Photography?

Blake Wood: Post-Photography is a style of art in which digital images are created through AI and machine learning. It coincides with the emergence of early AI collaborative tools like ArtBreeder, that works by remixing existing images uploaded by the artist and more recent tools like DALL•E 2 and Stable Diffusion, that convert text to pixels using deep learning and artists’ written prompts. Post-photography is post-camera. It can bypass the camera apparatus all together, learning and pulling from billions of images of humanity’s photographic history and then instantly composing an image from the artists’ desired prompt.

MBON: How do you think the photographic process changes when there is no physical subject?

BW: I think my photographic process changes in that my portraits can start with broader concepts i.e. memories, experiences, future events, but I’m still able to create a sense of closeness to the subject. When working with AI, I choose my location, tools and subjects. The true freedom I have to create anything can be daunting, because the possibilities are endless, but that ability alone opens you up to explore so many ideas that you would’ve never been able to otherwise.

MBON: How do you view the role of curation in the cryptoart space?

BW: Curation is extremely important in cryptoart. It helps identify artworks’ cultural value, quality of the work, its connection to art history and art movements, also displaying and arranging of the work itself, as well as educating a wider audience to new concepts within cryptoart in an intelligible way. Curation can also bring traditional art institutions, collectors and liquidity to the space, which strengths the ecosystem overall.

MBON: Who are some photographers working in post-photography you appreciate?

BW: The first photographer I came across that was exploring post-photography was GANBrood, aka, Bas Uterwijk. He was working with ArtBreeder in 2020, creating imagined portraits of people by remixing two or more image inputs. His portraits of historical figures before cameras existed really stand out to me. Another artist I appreciate is Claudia Pawlak, who creates botanicals with AI and prints these images as cyanotypes by hand. Prompt-based AI tools have reached the level in which outputs can be indistinguishable from traditional photographs. Artists are now exploring more and the post-photography movement is really growing.

MBON: When creating this new body work, do you find that the AI can express emotion, or, rather, are you instructing it to do that through specific prompting? Do you think machines have the capacity to feel?

BW: I’m fascinated by creating emotional depth in the portraits that I make when working with AI. There’s a common understanding that what makes us sentient beings primarily is the ability to empathize and express emotion, which AI lacks. I find that DALL•E 2, for example, understands emotional concepts to an extent. There’s a softness and a feeling of intimacy when using certain words. I gravitate towards creating images that reflect those human experiences and emotional connections. As we create more with AI, the greater its understanding of human emotions will be.

I’m fascinated by creating emotional depth in the portraits that I make when working with AI… I find that DALL•E 2, for example, understands emotional concepts to an extent. There’s a softness and a feeling of intimacy when using certain words.

— Blake Wood

“Canyon I” by Blake Wood, 2022

MBON: When did you start getting into crypto? What sparked your interest in NFTs?

BW: I was initially interested in Bitcoin in 2011 and even created a wallet on a thumb drive but couldn’t figure out the rest. The idea of using digital currency seemed like an obvious next step for the world. I got more involved in 2017 and, by 2020, I fully committed to learning crypto trading and DeFi. The first I heard of NFTs was in the summer of 2020, when CryptoPunks were being discussed by accounts that I followed on Twitter. Then in autumn 2020, I discovered NFT platforms and fell in love with the concept of art on-chain. The idea that NFT technology gave artists the ability to show provenance of their work and earn royalties in perpetuity was extremely empowering.

MBON: Tell us about how you started getting into photography? What environment shaped your artistic identity?

BW: Being a pensive, curious and creative child, photography was an easy way for me to make sense of things. When I was 11, my mother enrolled me in a summer course in photography. I borrowed my father’s Canon 35mm film camera from the ‘80’s to learn photography. I remember discovering the excitement of being able to create glimpses of the world as I saw it and how I wanted to remember it. Growing up in a small New England town, I was surrounded by enchanted forests, the magic of nature, and interesting characters. I had always felt different and, at 17, I moved to New York City to pursue my dreams and find like-minded souls. I went on to publish a monograph with TASCHEN of the portraits I created of my dear friend Amy Winehouse and had the honor of my work being acquired by the permanent collection of the National Portrait Gallery in London.

MBON: There is a lot of AI hate out there. People are scared the human hand will be completely replaced. Do you view your work with AI as collaborative? Where does your will start and the machine’s end?

BW: Humans have been working together with technology of some sort since the beginning of time. The hate for any new technology is part of the process of it being widely adopted. The work that I create with AI is completely collaborative. It’s my words, my structuring, my ideas and my feelings. I am very present in the art I make with it. AI allows you to collaborate and iterate in ways we’ve only dreamed of. Certain things are replaced by technology to make our lives more efficient, but art will always be something humans are driven to make regardless of what type of technology exists.

MBON: How does your training as a film photographer inform your work with AI? Tell us more about the process of prompting for you?

BW: The understanding of photography and all my techniques helps replicate what I do traditionally with film when working with AI. My life experiences and knowledge of art history, art theory, camera and technical skill, go into my AI work. I think that’s the beauty with prompting, you can really fine tune outputs. I start with composition and end with stylistic descriptors and tweak them until I get something that speaks to me. Every artist works with prompting differently. Exploring is a huge part of the fun of it.

“Amy Winehouse #1 – Memorial” by Blake Wood, 2009. Minted 2022.

Check out Wood’s AI photography available on SuperRare.

Tech

Out of the Vault and onto the Chain: the Evolving Nature of Provenance

SuperRare editor Oli Scialdone considers the social experience of provenance and its relationship with community in the Web3 space.

Curators' Choice

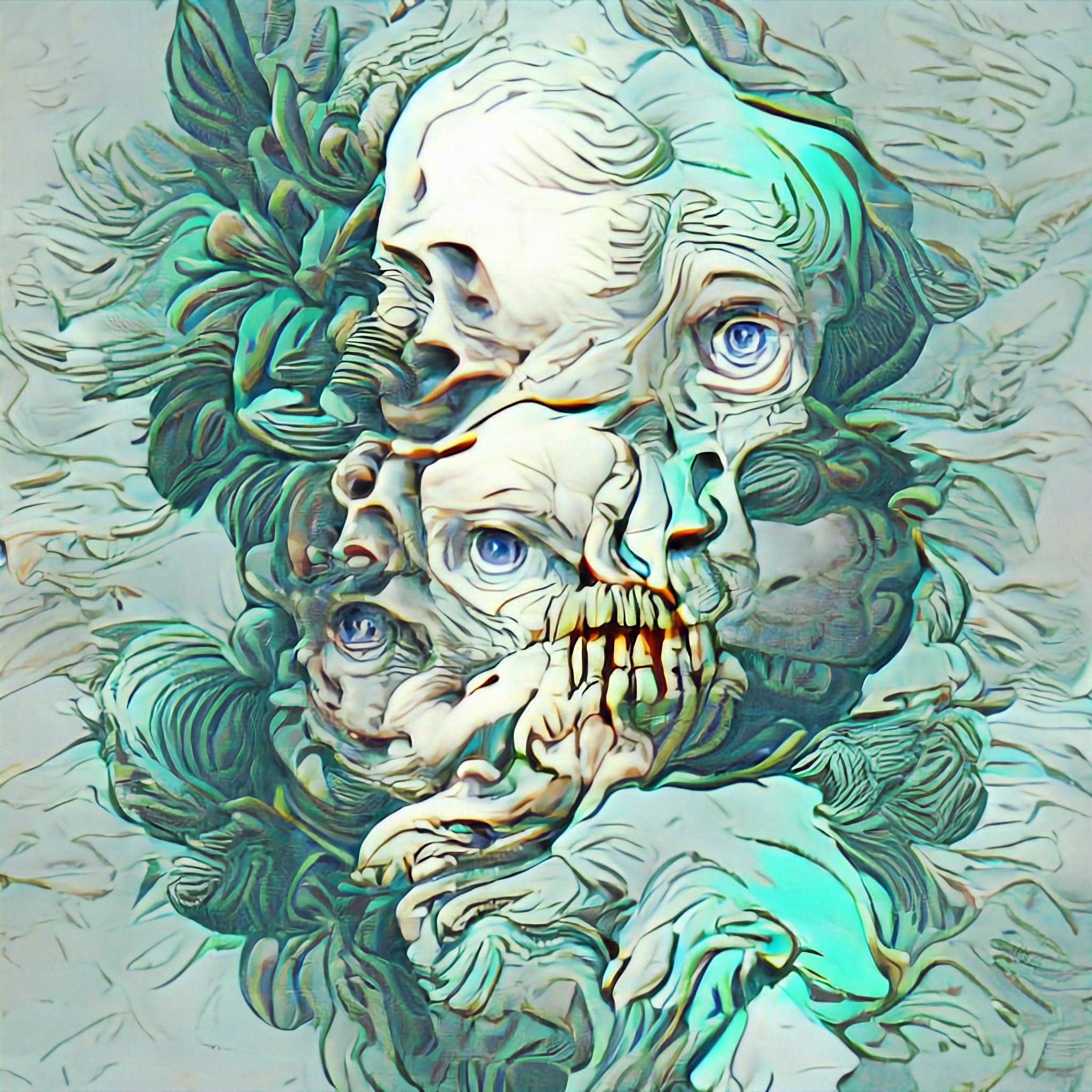

Curated Conversations: ALIENQUEEN

SuperRare Labs Senior Curator An interviews ALIENQUEEN about psychedelics, death, and her journey in the NFT space.